Solid

With concentration, he’s solid enough to wear a watch. Carry a briefcase. He can even put on a suit so long as his mind doesn’t wander. If it does, it all falls to the ground, and he has to painstakingly start over.

He likes to catch trains, though he has to be careful to sway as they accelerate and decelerate. He takes long walks, mostly at night, when he doesn’t have to worry about projecting a shadow. He might’ve stood right next to you and – barring a slight chill – you’d never have known.

But no matter what he says, all that emerges is a moan: a low, feeble sound reminding anyone within earshot he’s been dead far longer than he lived.

Fall

She has killed seven, all from heights. First she’d tried strangulation. Her hands were perpetually numb, though, and at a certain pressure they’d slip through her victims’ necks and into their mattresses.

But even as a ghost – when every movement is like a syrupy dream – she can manage a quick, brutal shove.

Her victims began, years ago, as men who looked like her killer; then men who mistreated their wives. Now they’re any man stupid enough to lean out over a railing, staring down at the city, listening to the soft song of traffic. Anyone who feels his stomach churn and the soles of his feet itch.

No one knows why they jump.

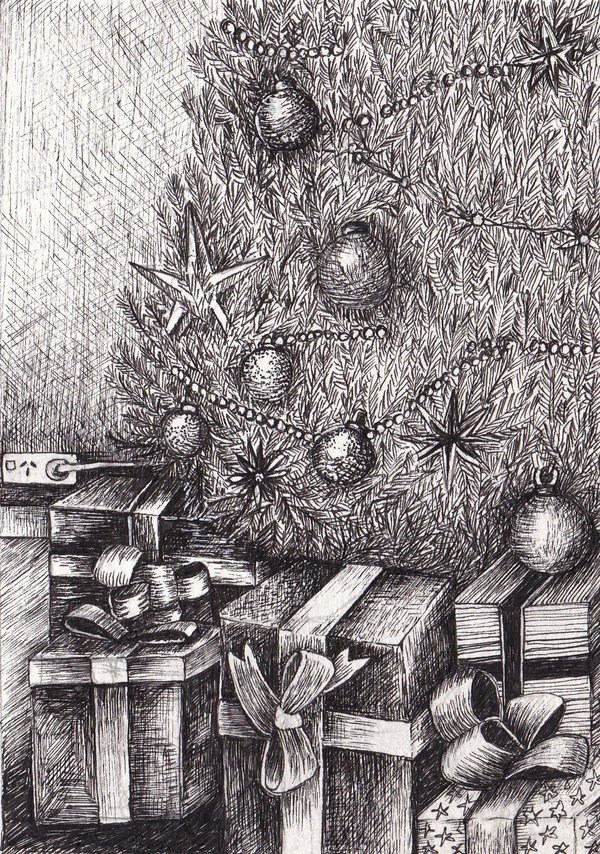

Christmas

He’d been dead a long time, but what was under the tree never changed. The same thoughtless junk. He tore ineffectually at the ribbons and wrappings, fingers fat and insubstantial; then he frayed at the gaudy lights until he exposed the wiring.

Upstairs, the family slept. Smoke woke the mother first, and she woke the father, and together they snatched the children from their beds. They were all soon out on the front lawn, ashen and weeping, staring at the roaring fire. They were holding each other so fiercely they’d be bruised come dawn.

This was his gift to them. Merry Christmas, he said, though no one could hear him.

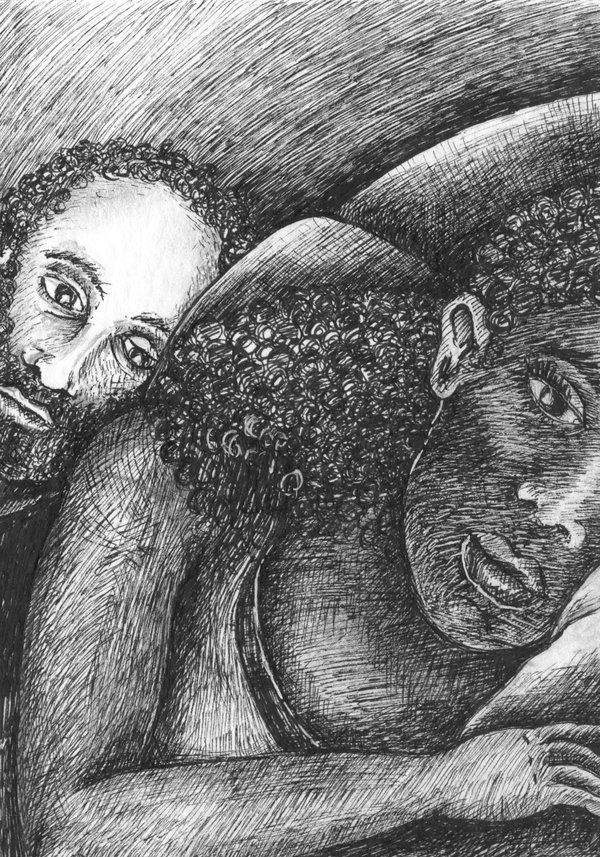

Henry

Henry, he says, day after day. Henry, I’m here. He writes it with his fingers in mirror-steam and knocks it on the furniture they bought together and whispers it like wind.

So far, Henry hasn’t noticed. Instead he lies in bed and stares at the ceiling. Friends call but are mostly ignored. He has long showers and he cries and cries. Every day’s meant to get easier, but it looks like it’s getting worse.

It has been like this since the funeral. (He didn’t attend, just wafted outside and waited.) It breaks his heart to see Henry like this. I love you, he says. He knocks it and writes it and whispers it and he swears he’ll do nothing else until Henry hears him. I’m right here.

Questions

Staring at his own dead body, still in its pyjamas, he feels embarrassed more than anything. Like he’s listening to his voice on tape or hearing himself snore. Heart attack, he guesses. It doesn’t hurt anymore.

He remembers his meds. Two green, one pink, like clockwork. The last time he stopped taking them was hell. He can’t even think about it – the things he did and said – without feeling its gravity again, its marrow-deep despair. Who is he without his meds? Will he be that way forever?

And without the meat and electricity inside his head, who’s even asking these questions? He sits down beside his corpse, wishing he could close its eyes. He waits for someone to find them.

Between

Whenever they embrace, she’s between them. She flits between their lips when they kiss. In bed, if the couple lie face-to-face, she drinks in that intimacy too.

They wonder what happened, though they don’t speak of it as that would make it real. Aren’t they the same people who met, years ago? Hadn’t they only become closer? Now when they tell each other I love you, she’s there, invisible, to suck all the truth from their words.

Once their love is gone, she’ll move on to another couple. They’ll look into each other’s eyes and not notice the ghost between them, trying to remember what it was to be loved.